Related Products

For Professionals

- Amplification

- Assessment of Student Skills, Challenges, Needs

- Early Childhood: Infants, Toddlers, Preschool

- Hearing Loss – Identification, Impact and Next Steps

- IDEA Law Summary Information

- Language and Speech Development Issues

- Legal Issues in Serving Children with Hearing Loss

- Listening (Auditory Skills) Development

- Planning to Meet Student Needs

- Self-Advocacy Skills for Students with Hearing Loss

- Self-Concept: How the Child with Hearing Loss Sees Himself

- Social Skills

- Speech Perception & Learning

Related Teacher Tools Takeout Items

Auditory Identification

AUDITORY SKILLS FOR SCHOOL SUCCESS

Auditory Identification

Speech perception is the set of listening skills that are essential for communicating by spoken language. Speech perception skills can be described in four categories: awareness, discrimination, identification and comprehension. Each skill set is described on web pages in the Listening (Auditory Skills) Development section.

Speech perception is the set of listening skills that are essential for communicating by spoken language. Speech perception skills can be described in four categories: awareness, discrimination, identification and comprehension. Each skill set is described on web pages in the Listening (Auditory Skills) Development section.

These listening skills do not develop sequentially from one category to the next. Rather, a child might simultaneously be developing skills in two, three, or even all four categories, but at varying levels of complexity.

Speech perception training also requires attention to the complexity of the listening task, or the amount of acoustic information in the message. Generally, levels of complexity are described as the sound/phoneme level, word level, phrase/sentence level, and discourse/connected speech.

An auditory identification task asks the student to name what was heard – by repeating, writing, or pointing to text or a picture. The daily listening check LINK is an identification task that asks the student to repeat which of six sounds (or silence) was heard. Giving other information about a spoken utterance may also be an auditory identification task: naming the number of syllables or words, the stressed syllable, the first sound, the last word, etc.

Auditory Identification and Students with Hearing Loss

Auditory identification requires the student to perceive the vowels, consonants and sometimes, the stress pattern of what is spoken.

Examples of Common Identification Tasks

A first grader looking at the words tub, tube, cub and cube is asked to point to the word she hears. This decoding task also requires her to hear and identify the initial consonant and the vowel sounds of the stimulus word.

People discussing different opinions

A high school teacher asks students to explain some cultural differences in northeastern and western Africa. To answer correctly, the student needs to hear and identify the initial consonant-vowel combinations of two key words: northeastern (not southeastern or southwestern) and western (not eastern).

During a listening check, the adult says “oo” and the student responds “m”. One may conclude that the student detected, or heard, the adult’s voice, but did not perceive the sound correctly and therefore made an error in identification of the phoneme.

Evaluating the Acoustic Similarities of Phonemes and Words

The professional working with students who are deaf or hard of hearing – especially those using listening and spoken language — should be able to evaluate the acoustic properties of a spoken utterance and determine how to best help the student be successful with a given listening task. Here are some guidelines.

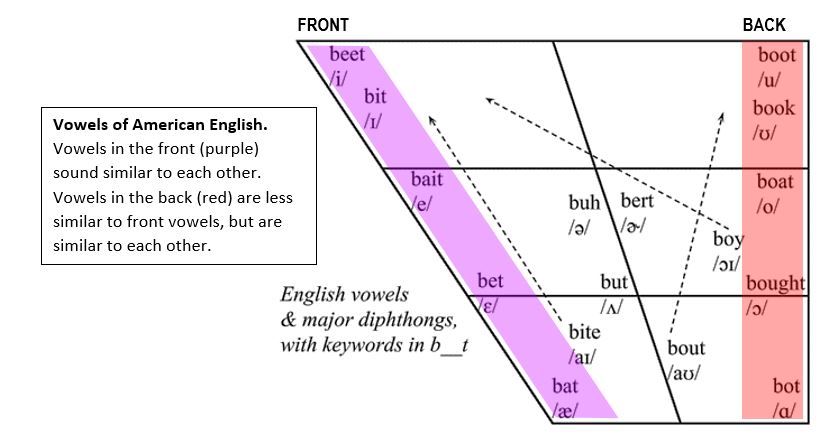

Vowels

- Vowels generated primarily in the same area of the vocal tract (front or back, high, mid or low) are more acoustically similar to each other than to other vowels.

- A diphthong is a vowel that glides from one sound to another and is easier to distinguish from the non-diphthong vowels than the non-diphthong vowels are to each other.

- Long i (bite) glides from -o- (bot) to ee (beet)

- Long a (bait) glides from -e- (bet) to ee

- ou (bout) glides from -o- (bot) to -oo- (book)

- oi (boy) glides from aw (bought) to ee (beet)

Consonants

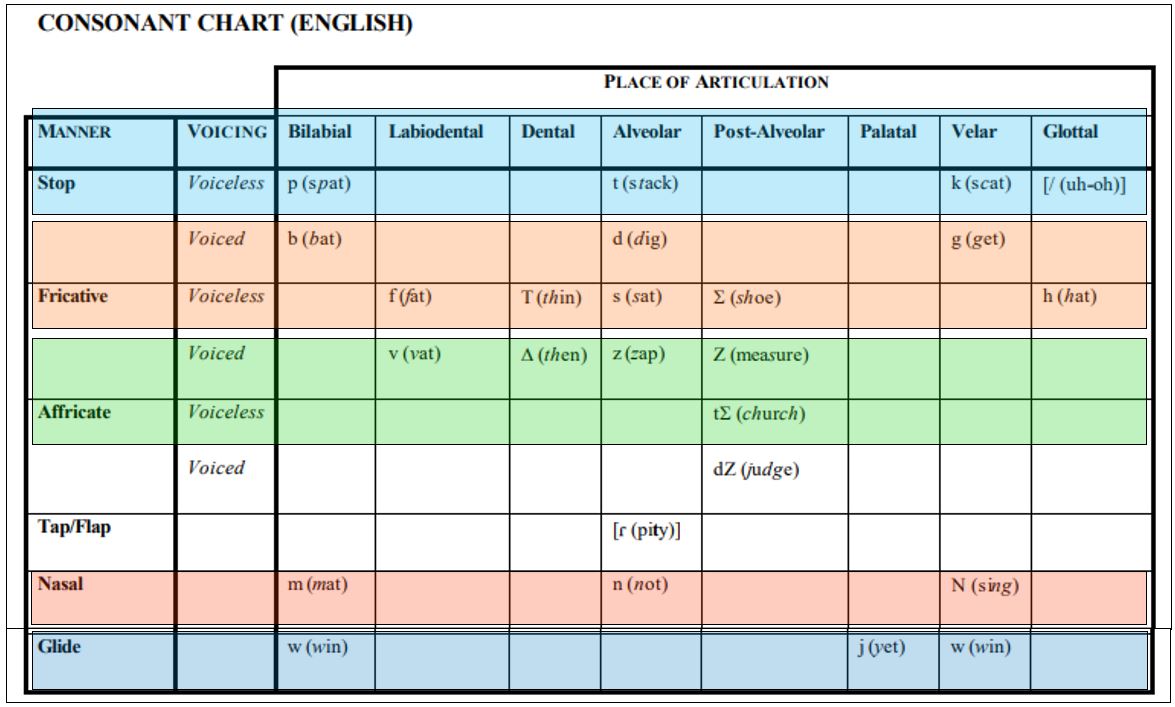

Consonants that are similar in manner (occurring in the same row on the Consonant Chart) are more similar to each other than consonants on other rows in the chart.

Identification errors are more common when students with hearing loss are listening to solely fricatives and affricates. (Erber, 1982)

Words that contain several nasals and glides (m, n, r, l, w,y) can be difficult to identify using hearing alone.

English Consonant Chart by the University of Arizona. Consonants produced in a similar manner, such as Fricatives, are more difficult to distinguish from each other, but easier to distinguish from consonants produced in a different manner, such as Nasals.

Informal Assessment of Auditory Phoneme & Word Identification Skills

Formal assessment of speech perception skills should be performed by a trained audiologist using a “battery of tests … in order to provide a comprehensive assessment of a child’s capabilities.” A teacher with concerns about a student’s perception of phonemes and words can gain information about his ability to identify vowels and consonants using Indiana University’s Minimal Pairs Test. This information can be helpful to the professional in determining what auditory objectives can be selected for practice.

A student’s speech production can also give us information about his speech perception, so one method of informal assessment is to listen to what the student says. Is he substituting /ch/ for /j/? Are his vowels hard to distinguish? Make notes of those errors, and use them to guide your assessment. For an informal evaluation, write each phoneme you want to check (for example /d/ and /j/) on a card. Using an auditory hoop, present each phoneme several times and have the student repeat what he hears and point to its letter. If he both repeats incorrectly and points to the wrong letter, he has misheard the sound – an auditory error. If he points to the correct letter but says the incorrect phoneme, his error is in speech production, not auditory identification. If he says the correct phoneme, but points to the incorrect letter, it may be a phonics error, not an auditory error.

Improving Auditory Identification of Phonemes and Words

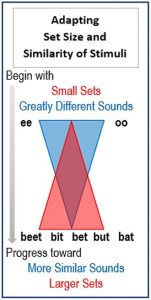

To prepare for practice with auditory identification the teacher will select the stimuli to be used and select a student response task. During the lesson, the teacher will respond to errors and adjust the difficulty of the task to ensure student success with the skill. The size of the set can be increased if the task was easily mastered or decreased if it was too difficult. The difficulty can also be decreased when selecting the phonemes and words for each set. Phonemes that are more similar to each other (and words that contain similar phonemes) will make identification more difficult.

To prepare for practice with auditory identification the teacher will select the stimuli to be used and select a student response task. During the lesson, the teacher will respond to errors and adjust the difficulty of the task to ensure student success with the skill. The size of the set can be increased if the task was easily mastered or decreased if it was too difficult. The difficulty can also be decreased when selecting the phonemes and words for each set. Phonemes that are more similar to each other (and words that contain similar phonemes) will make identification more difficult.

Improving Auditory Identification of Phonemes and Words – Selecting the Stimuli

Many auditory development curricula, like the CID SPICE or CAST, structure lessons by beginning with sets of two stimuli that are very different from each other acoustically. As skills progress, the size of the set is increased and the stimuli become more similar (and possibly more complex). When the student is successful with a fairly large set of very different words, then words that are more acoustically similar can be selected. It may be necessary to return to a small set size when the auditory task becomes more difficult.

Many auditory development curricula, like the CID SPICE or CAST, structure lessons by beginning with sets of two stimuli that are very different from each other acoustically. As skills progress, the size of the set is increased and the stimuli become more similar (and possibly more complex). When the student is successful with a fairly large set of very different words, then words that are more acoustically similar can be selected. It may be necessary to return to a small set size when the auditory task becomes more difficult.

Refer to the consonant and vowel charts above to clarify the following example.

Example of Examining Similarity of Acoustic Content of Words

Set of 2 Words with very different acoustic content.

stimuli: comb vs wish

CONSONANTS

comb /k/ voiceless velar, /m/ voiced nasal (low frequency)

wish /w/ voiced glide, /sh/ voiceless fricative (high frequency)

VOWELS

comb /oa/ back

wish /-i-/ front

Improving Auditory Identification of Sentences and Discourse

The same principle of adapting set size and acoustic similarity of the stimuli applies when practicing auditory identification of longer stimuli. For these tasks, the teacher will consider these acoustic properties of the stimuli.

The same principle of adapting set size and acoustic similarity of the stimuli applies when practicing auditory identification of longer stimuli. For these tasks, the teacher will consider these acoustic properties of the stimuli.

Length of the utterance (number of syllables) — Identification may be more difficult when all choices have the same number of syllables.

Similarity of the key words (vowels, consonants and number of syllables) — As explained above, similarities among phonemes can make identification more difficult.

Number of key words – Poor auditory memory can cause stimuli with more key words to be more difficult to identify.

Position of key words – (first word, medial or last word in utterance) Key words are more easily identified when they occur at the beginning or end of a sentence, rather than in the middle.

Amount of contextual or visual support (e.g. choosing from sentences provided in print, discussion about a picture, discussion about a specific topic, or questions about and a variety of topics) Identification is made easier in the presence of context cues such as printed choices, or a picture or a single known topic to talk about.

Listening for Words within Sentences – Selecting the Stimuli

When listening for words within longer utterances, the linguistic context in which a word appears contributes to identification. For example, if a student is asked to repeat the word “doctors,” she may incorrectly say “lockers.” If the same word appears in a discussion about community workers, however, the student who thought she heard, “Lockers spend years in college to earn a medical degree” will probably infer that the speaker actually said doctors, not lockers. (This is assuming the student has the background knowledge that doctors earn medical degrees.)

When listening for words within longer utterances, the linguistic context in which a word appears contributes to identification. For example, if a student is asked to repeat the word “doctors,” she may incorrectly say “lockers.” If the same word appears in a discussion about community workers, however, the student who thought she heard, “Lockers spend years in college to earn a medical degree” will probably infer that the speaker actually said doctors, not lockers. (This is assuming the student has the background knowledge that doctors earn medical degrees.)

The content of a sentence can also contribute to the difficulty of identifying a specific word within the sentence. If the target word is embedded in a carrier phrase, like “Show me the ____”, it will be easier to identify than if it occurs within a unique sentence. Consider these examples.

Example A. The teacher says, “Show me the elephant.” Student points to elephant.

Example B. The teacher says, “The circus performer rode an elephant,” then asks, “What did the circus performer ride?”

Example C. The teacher says, “The elephant was ridden by the circus performer,” then asks, “What did the circus performer ride?”

Example A is a multiple choice task, the least difficult of the examples. The student is looking at a set of pictures or objects and chooses the picture that matches the word that was said. The key word also falls in a predictable location in the sentence. Key words at the end of a sentence are more easily identified due to the absence of a word following it. It is recommended that in addition to pointing, the student be required to repeat the word. This promotes the student’s self-monitoring of his own speech production. An error in speech production, however, should not be counted as an error in auditory perception.

Example B is more difficult than Example A because the student is unaware of the position of the key word until after the sentence has been spoken and the question is asked. The teacher could have asked, “Who rode the elephant?”

Example C is the most difficult of the three examples. The key word is unknown to the listener until the question is asked and it occurs in the middle of the sentence where it is affected by coarticulation with the surrounding words. Furthermore, the sentence is in the passive voice, which is challenging for students who are learning spoken language.

Sentence Identification – Selecting the Student Response Task

Sentence identification tasks can require a variety of responses. Examples of responses, from easiest to more difficult, are:

- choose the sentence that was heard from a set of written sentences

- complete a partial sentence

- repeat the sentence word for word (“tracking”)

- write the sentence

Writing the sentence is the most difficult of these tasks because in addition to memory, spelling and fine motor skills are accessed, increasing the cognitive complexity of the task.

When a student is asked to repeat a sentence word for word, the student’s auditory memory and working memory will affect her success with the task. Some teachers report, for example, that students who were asked to recall and repeat a list of spoken words were able to repeat fewer words when those words had more than one syllable

Repeating the sentence may also contribute to language improvement by requiring attention to the ‘little’ words (e.g., the, to, in, etc.) that are often barely audible in spoken language and frequently omitted in the language of some students with hearing loss. Practice with continuous discourse tracking can promote awareness of those little words.

Continuous discourse tracking provides practice with auditory identification practice at the phrase or sentence level. The process was recommended by DeFilippo et al (1978).

- The teacher, using an auditory hoop to prevent speechreading cues, reads aloud from a text within the student’s language level. The length of the each spoken segment is also determined by the teacher based on the student’s language level, auditory memory skills and attention.

- The student repeats verbatim what is heard. When the student makes an error, the teacher repeats the portion of the segment that includes the error until the student repeats correctly.

- This procedure is followed for a timed interval of three to five minutes. At the end of the interval, the number of words correctly repeated is divided by the number of minutes to obtain a words per minute score. By graphing this score for each session, the student and teacher can see an improvement in speech perception over time.

DeFilippo suggests limiting the repetitions to three so as to avoid frustration. Any words that weren’t repeated by the student are marked as an error and not included in the count of words repeated.

By requiring the student to repeat each word and morpheme (e.g. -ed, -s), the student is required to attend closely to these important linguistic markers. This may contribute to improvements in the student’s spoken language skills.

Practicing Auditory Identification – Structuring the Lesson

Teach and learn words written on two pieces of puzzle

After establishing the need for practice, selecting the stimuli and choosing a task (when necessary), most auditory identification lessons follow these steps, with the exception of continuous discourse tracking previously described.

The teacher explains the objective of the lesson and describes any strategies that will help the student be successful.

(If using pictures or text for the student to look at) The teacher places the stimuli in front of the student. The student names or reads each item. The teacher clarifies any errors. If clarification cannot be made, that item is removed. (If using pictures of text for the student to look at).

The teacher ensures she has the student’s attention, then points to each item and names it or reads it. At this time, the student is allowed to use speechreading cues.

The teacher raises the auditory hoop to cover her entire face and says the phoneme, word, phrase, or sentence. The student responds by pointing to the item and/or repeating it. Even when asked to point to the correct item, the student should also repeat it to provide practice in self-monitoring, speech production, and language development.

If the student’s response is correct, the teacher gives praise. If it is incorrect, the teacher repeats the stimulus. If the response is still incorrect, the teacher may repeat the stimulus with an adaptation such as:

- Speak more slowly

- Exaggerate a salient feature of the stimulus

- Allow speechreading (do not use the auditory hoop)

If the response is still incorrect after the third repetition, then point to the correct item while repeating the word. If the student continues to struggle in subsequent trials, reduce the size of the set or change to a discrimination (same or different?) or detection task to allow the student to be successful.

Regardless of the student’s level of success, provide positive feedback and discuss strategies.

Practicing Auditory Identification — Adapting the Difficulty of the Task

During practice, the student’s most recent response may lead to an adaptation of the next task. If the student responded without effort to the previous task, the teacher may choose to make the next task slightly more difficult to allow the student to remain successful while being challenged to improve auditory skills.

During practice, the student’s most recent response may lead to an adaptation of the next task. If the student responded without effort to the previous task, the teacher may choose to make the next task slightly more difficult to allow the student to remain successful while being challenged to improve auditory skills.

Increasing the Difficulty

Erber describes strategies to make a task more difficult.

Choose words or phonemes that are more acoustically similar.

Speak more quickly and naturally.

Move further from the child.

Add background noise.

Increase the size of the set.

Give two stimuli at a time, student should repeat and point to both.

Embed words or phonemes in a carrier phrase such as, “Show me ____.”

Decreasing the Difficulty

When the goal is improvement of auditory speech perception it is important to give feedback and supports to help the student be successful. If a student is struggling, pause from the exercise to provide that support. Point out the special features of the words or phonemes that might make them easier to identify. Use visual and tactile cues to make the differences between the sounds more salient. Praise the student’s efforts and set a goal for the end of the lesson.

Example of providing support for student struggling to identify /ch/ and /sh/

“Can you feel the tongue pushing the roof of your mouth when you say /ch/? Try it. [Student produces /ch/] Now say /sh/. The tongue stays down [Student produces /sh/.] Did you feel that? …Okay, we’ll do two more. Remember to listen for that tongue pushing.”

It’s a good idea to end each lesson with a successful task. Adapting the task can help a student be more successful, less frustrated and more willing to participate in the next auditory challenge. Here are some ways to reduce the difficulty of a task.

Repeat the stimulus, more clearly and slowly.

Highlight distinguishing features of the stimuli.

Allow speechreading.

Reduce the size of the set.

Choose words or phonemes that are less similar.

The goal is for the student to identify words or phonemes with 80% accuracy in an open set without regard to the acoustic content. This goal, however, may not be attained by all students, based on a variety of factors. If the task was identifying phonemes or words, ask yourself , In what real life situation will the student need to correctly identify this word in isolation, with no contextual clues at all? If the challenging task was identifying or tracking sentences or discourse, perhaps the student would benefit from practice applying strategies for communication repair. LINK

Always remember two key principles: This is teaching, not testing and end on a high note with a correct response. .

More Resources for Auditory Identification

Free webinars from CID – Central Institute for the Deaf

Continuous Discourse Tracking

Continuous Discourse Tracking

KTH software is “a sentence-level speech-perception training program designed to help the client develop awareness of sensory information, contextual evidence, and improve auditory listening skills. … (A) story is read by the clinician a line at a time, requiring the client to repeat it back verbatim.” Provides extensive data. Free download, funded by federal government grants. .

References

De Filippo et al 1978) C L, Scott B L. A method for training and evaluating the reception of ongoing speech. J Acoust Soc Am. 1978;63(4):1186–1192.

Erber, N. 1982 Auditory Training. A.G. Bell Association for the Deaf. Washington D.C.

CURRICULA

Auditory Skill Development Cards for Classroom Listening (No Glamour Auditory Processing Cards)

CAST – Contrasts for Auditory and Speech Training

SPICE – Speech Perception Instructional Curriculum & Evaluation

SPICE to Life Auditory Learning Curriculum

Posted August 2019. This information was authored by Julia West, teacher of the deaf/hard of hearing who has taught students with hearing loss in private and public schools for over 20 years. She is co-author of the CID SPICE for Life Auditory Learning Curriculum and authors the Listening and Self-Advocacy sections of the Teacher Tools e-Magazine.