Related Products

For Professionals

- Amplification

- Assessment of Student Skills, Challenges, Needs

- Early Childhood: Infants, Toddlers, Preschool

- Hearing Loss – Identification, Impact and Next Steps

- IDEA Law Summary Information

- Language and Speech Development Issues

- Legal Issues in Serving Children with Hearing Loss

- Listening (Auditory Skills) Development

- Planning to Meet Student Needs

- Self-Advocacy Skills for Students with Hearing Loss

- Self-Concept: How the Child with Hearing Loss Sees Himself

- Social Skills

- Speech Perception & Learning

Related Teacher Tools Takeout Items

Study Skills for Children who are DHH

Study Skills word cloud on green background

| Research2,3 indicates that healthy executive function skills do not require hearing. Age-appropriate language proficiency, whether in sign or speech, is crucial for the development of healthy executive function skills. The greater the language delay the greater the probable need for development of executive function skills. There is also research4 that indicates if a preschool child with hearing loss scores within the normal range in language skills, but exhibits executive function issues, it is predictive of subsequent language development issues. |

All Children need direct teaching of study skills so they can efficiently process the information they encounter in school. Executive function issues require direct teaching in study skills. Students with hearing loss can benefit greatly from strategies to help them stay focused on tasks to do. Read on for more about executive function and specific study skills strategies.

Study skills help us manage tasks. People with executive function issues need greater attention to study skills. Executive function refers to mental skills including1 working memory, flexible thinking, inhibition/self-control including controlled attention. Executive function is responsible for many skills, including:

- Paying attention

- Organizing, planning, and prioritizing

- Starting tasks and staying focused on them to completion

- Understanding different points of view

- Regulating emotions

- Self-monitoring (keeping track of what you’re doing)

Students with hearing loss often have difficulty with many of the items listed above, secondary to missing part of communication messages and continually trying to catch up and keep up. Structure is often key to the success of our students, in terms of predictable learning routines and expectations. Yet, outside structure alone will not compensate for the extra organization and strategies our students need to keep pace with their peers.

Below is a list of study skills in context to the broader areas of learning. 5

| Activities Related to Learning | Study Skills Strategies |

| Processing information |

|

| Retaining and recalling information |

|

| Organizing materials and managing time |

|

| Selecting, monitoring, and using strategies |

|

Strategies to Build Better Study Skills

The time-honored quotation, “When the student is ready, the teacher will come,” reassures that learning will happen when the time is right. Unfortunately, our standards for teaching and learning are not set up to patiently wait for that time! Learning requires students to assimilate and generalize information in quick order. For many of our students who are deaf or hard of hearing, the explicit teaching of study skills will help them become “ready.”

Learning styles, personality traits, interests, motivation, energy level – each student comes with a jumble of these variables. Keep in mind these personal characteristics in determining which study skills to promote and practice.

Organizational Strategies

Organization is key. Helping our students become organized begins at the earliest stages of development. Review these tools for fostering language and cognition, the “pre-study skills” of a study skills curriculum.

Sorting and categorizing: Emergent language learners are surrounded by disconnected sights and sounds. Structure the environment with items to sort (color, shape, size) or categorize in groups (types of animals, cars, toys).

For older students: group multiplication facts by number; group story events by beginning, middle or end; or group historical events by country or decade or impact.

Break it down: Prevent the learning task at hand from becoming a drudgery by breaking it down into small parts. Those multiplication facts are overwhelming unless taken one number group at a time. Drill and practice are most effective if kept in small doses.

Using a Planner: These come in a variety of shapes and sizes and are worthwhile aids for many students. At best, they foster independent study skills. At worst, they become one more skill to learn in an already overloaded heap. Recognize what your student is capable of fitting into his or her study schedule and introduce sparingly.

Clean Workspace: No extraneous devices allowed! The first rule for students of all ages is to keep distractions at a minimum. Provide a designated area in the classroom or home that is well-lit, quiet, and dedicated to studying.

Comprehension Strategies

Study skills provide the framework for comprehension: their strategies go hand-in-hand. Working on auditory memory to improve retention and recalling information is a natural goal when working with DHH students.

Retelling: Once we tell something in our own words, we begin to implant it in memory. Retelling is a powerful comprehension and study strategy when carefully matched to communication abilities, attention, and interests. Ask young students, “what happened?” and wait, patiently, for the response. For older students keep your questions specific and structured: instead of asking, “What happened in school today?” ask for the details: “Tell me three new spelling words;” or “tell me 3 things that happened in science,” or “What are 3 things that happened in the story?” Start small and build on the responses.

Visualizing: Another powerful strategy to stimulate memory and learning is to provide students with visual cues. Take full advantage of manipulatives, videos, photographs. Language experience stories (pairing pictures with the steps of a science experiment or social studies chapter or fieldtrip) give students visual reminders. If your only device is paper and pencil, a “quick draw” sketch activates memory and prompts conversation: “Did you actually see bugs in the science lab? Is that a molecule? What are these parts?”

Memorization: Memorizing just for the sake of memorizing, without context, may be outside the sphere of critical thinking and learning, yet there are times when facts need to be memorized. There are ways to make memorization less tedious: mnemonics (remembering a list of facts by the first letter of each word such as the names of the Great Lakes: “Super Man helps every one!”), flash cards, treasure hunt to find fact cards, rewards for progress goals, homemade game boards. The bottom line: make goals achievable, make the activity fun, and make the reward worthwhile to the student.

Writing on paper versus typing on a screen: Researchers suggest that the physical act of writing on paper increases focus and critical thinking. Henriette Anne Klauser, Ph.D.6, believes that writing on paper triggers and

activates the brain to “wake up! Pay attention!” Writing may seem tedious to students when curriculum has been centered on computers and tablets, yet It makes good sense to incorporate writing on paper as one of many options.

activates the brain to “wake up! Pay attention!” Writing may seem tedious to students when curriculum has been centered on computers and tablets, yet It makes good sense to incorporate writing on paper as one of many options.

Taking Notes: Whether a student is writing on paper or typing on a de

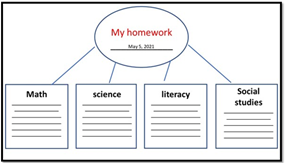

vice, the act of taking notes is a skill that requires practice. Provide note-taking materials and directions prior to a video or presentation and options (planner, targeted computer file, PPT handout, etc.) for filing and organizing the information when completed. Graphic organizers designed ahead of time can provide designated spaces for students to write down things to remember and learn. Use these notes to retell and reflect on the event so the purpose for taking them is recognized.

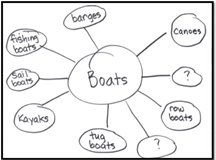

Graphic Organizers: These are invaluable in breaking down information, visualizing, organizing, simplifying, mapping. There is no need to rely on

premade materials: simply draw circles or boxes to separate ideas, facts, number families, and there you have it! Find patterns to copy online or use suggested graphic organizers below to adapt and personalize.

premade materials: simply draw circles or boxes to separate ideas, facts, number families, and there you have it! Find patterns to copy online or use suggested graphic organizers below to adapt and personalize.

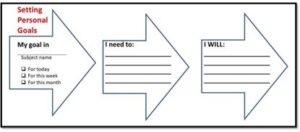

Motivation

The heart of self-determination is personal goal setting. The more you allow students to establish their own goals for learning, the more motivated and  successful they will be. Writing personal goals gives students a sense of control, self-awareness, confidence. Help your students set up attainable daily or weekly goals and use charts or graphic organizers to visually show progress.

successful they will be. Writing personal goals gives students a sense of control, self-awareness, confidence. Help your students set up attainable daily or weekly goals and use charts or graphic organizers to visually show progress.

Motivation to persist with any task relies on your student’s attention span. After five or ten minutes, take a break! For students who need activity, give them a chance to move their bodies or run around the playground. For students who need to be calm, do some coloring or painting.

Remember to provide rewards (tangible or intangible) for time spent on task even when learning the facts or concepts is not yet accomplished. The primary goal of a study skills curriculum is to establish the routine of studying. The mastery of information to be learned will be its own reward.

See some materials in Teacher Tools Takeout that relate to areas of study habits include:

Self-Advocacy: Predict, Plan, Prepare

Advocacy – Steps to Self-Advocacy Success Goal Review

Vocabulary Development – Attributes – All in Good Time

References:

- https://www.understood.org/en/learning-thinking-differences/child-learning-disabilities/executive-functioning-issues/what-is-executive-function

- Figueras, Edwards, Langdon (2008). Executive Function and Language in Deaf Children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13:3, 362-377.

- Hall, Eigsti, Bortfeld, Lillo-Martin (2018). Executive Function in Deaf Children: Auditory Access and Language Access. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61, 1970-1988.

- Kronenberger, Xu, Pisoni (2020). Longitudinal Development of Executive Functioning and Spoken Language Skills in Preschool-Aged Children with Cochlear Implants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63, 1128-1147.

- https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/ss2/cresource/q1/p01/.

- Henriette Anne Klauser, PhD https://srcxp.com/why-writing-is-important-for-students/#:~:text=Below%20are%2043%20of%20the%20reasons%20why%20writing,you%20have%20to%20talk%20to%20someone%20in%20person.