Related Products

For Professionals

- Amplification

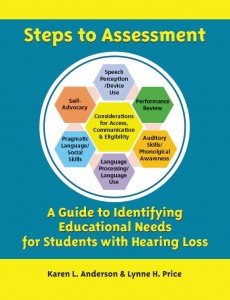

- Assessment of Student Skills, Challenges, Needs

- Early Childhood: Infants, Toddlers, Preschool

- Hearing Loss – Identification, Impact and Next Steps

- IDEA Law Summary Information

- Language and Speech Development Issues

- Legal Issues in Serving Children with Hearing Loss

- Listening (Auditory Skills) Development

- Planning to Meet Student Needs

- Self-Advocacy Skills for Students with Hearing Loss

- Self-Concept: How the Child with Hearing Loss Sees Himself

- Social Skills

- Speech Perception & Learning

Related Teacher Tools Takeout Items

Low Incidence ≠ Low Priority: A Court Case You Need to Know About

Miguel Perez, now a deaf adult, is seeking monetary damages under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

The aides assigned to provide sign language services were either unqualified or absent from the classroom for hours. Miguel was advanced to the next grade level based on inflated grades that misrepresented his actual progress, resulting in earning a Certificate of Completion rather than a Diploma, an unexpected outcome to him and his parents. His family sued the school district under the provisions of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and were awarded compensatory training post high school, but they were concerned about the life-impact of his poor education. Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools is the first case to determine if monetary damages under ADA would also be a possibility. After an appeal, the U.S. Supreme court ruled that Miguel can sue for “backward-looking” damages under ADA without exhausting the procedures of IDEA first. Read more on this important case and the realities of their responsibilities to the field of deaf education.

The IDEA Settlement Before Case No. 21-887, Miguel L. Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools – A WIN for Deaf Education

On March 21, 2023 the United States Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Michigan Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of Miguel Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools. The Supreme Court’s decision now allows families to bring an ADA claim “without first exhausting all of IDEA’s administrative dispute resolution procedures.”

Case History

Miguel Perez, a nine year-old deaf student, qualified for an IEP in 2004 in the Sturgis Public Schools after his family emigrated from Mexico. From ages nine through twenty, the district provided Miguel with “aides to translate classroom instruction into sign language.” Miguel and his family allege that for years, the aides assigned to provide sign language services were either unqualified or absent from the classroom for hours. They further allege that Miguel was advanced to the next grade level based on inflated grades that misrepresented the progress, or lack thereof, he was making. These misrepresentations led the family to believe that Miguel would graduate with his high school diploma. However, months before graduation, the family learned that Miguel would not be receiving a diploma, instead, he would receive certificate of completion. The family’s response was to then file a complaint with the Michigan Department of Education. They alleged that Sturgis had “failed its duties under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and other laws.”

The case was settled before it reached an administrative hearing. Under the terms of the settlement, Sturgis promised to provide Miguel all the “forward-looking equitable relief he sought, including additional schooling at the Michigan School for the Deaf.”

Implications for Deaf Education in the IDEA claim that Miguel was denied a Free and Appropriate Public Education

Shortages of personnel

Deaf Education as a whole has a long and chronic history of shortages of qualified Teachers of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (TODHH) and Interpreters, whether in a big city or a small town. However, IDEA requires that students whose IEP stipulates the need for access to instruction through either a TODHH or an Interpreter, or both, receive those services by qualified professionals regardless of personnel numbers. Further, those services which are deemed appropriate cannot be denied based on whether the school has the immediate personnel to provide said services. See IDEA.

Deaf Education as a whole has a long and chronic history of shortages of qualified Teachers of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (TODHH) and Interpreters, whether in a big city or a small town. However, IDEA requires that students whose IEP stipulates the need for access to instruction through either a TODHH or an Interpreter, or both, receive those services by qualified professionals regardless of personnel numbers. Further, those services which are deemed appropriate cannot be denied based on whether the school has the immediate personnel to provide said services. See IDEA.

This is the intersection between what is guaranteed by law, and what actual resources there are to provide services needed.

Sturgis is a town with a population of roughly 11,000 in 2004 when Miguel Perez and his family arrived in Michigan, and the population has grown by very little. Sturgis is surrounded by towns roughly the same size, with the nearest larger towns (Grand Rapids, Lansing) 95 miles away, and Detroit, the largest city at 150 miles away. In 2004, remote interpreting was not as prevalent as it is today, and highly specialized staff in the immediate area was unlikely to be found. Further, because deafness is a low-incidence disability, the needs of a single d/Dhh student can be at the bottom of a long list of concerns. However, as Miguel Perez and his family have proved, low incidence does not equal low-priority.

Advocating for appropriate services and supports and the argument for a TODHH

Nowhere in the summary of the IDEA complaint written by the Supreme Court of the U.S. is there a mention of a Teacher of the d/Deaf or hard of hearing (TODHH). Having a TODHH on the IEP team is necessary and critical to evaluating and monitoring the progress of d/Dhh students. Often in small schools the TODHH is looked to for expertise in all things related to serving d/Dhh students, whether they are truly experts or not. The TODHH is often the advocate for the student using data gathered in order to make recommendations to the IEP team that are appropriate. See Why a TODHH.

Good grades do not equal progress

During Perez’s school career, he was given grades that were not truly representative of his abilities. This is why assessment, tracking, and monitoring student progress is crucial to determining effective programming. The defined purpose of IDEA: to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free and appropriate education (FAPE) that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment and independent living. Tailoring assessment for d/Dhh is necessary to determine his or her unique needs.

Good relationships with families

Good relationships with families are paramount. There are times when even the itinerant TODHH is the person with whom the family places their trust and contacts first when there are concerns. Often, this occurs when teachers work with the same students year after year. Be as transparent as you can when there are concerns. When there are successes, even small ones, let the parent(s) know. That positivity may go a long way to nurturing parents’ experience with a school.

Summary

Before the IDEA case went to administrative hearing, both parties reached a settlement. Sturgis “promised to provide Mr. Perez all the forward-looking equitable relief he sought, including additional schooling at the Michigan School for the Deaf.” But at the time of his graduation, independent living after high school was out of reach. The district had failed in equipping Miguel with the knowledge and skills he needed to support himself. And now that the Circuit Court’s decision was reversed in regard to ADA, Miguel is free to pursue his lawsuit seeking damages from Sturgis Public Schools under ADA.

Calls to Action

Shortages of Personnel: keep communication lines open

- Keep your supervisors updated of situations where there are shortages.

- Keep your supervisors updated of how you are addressing those shortages and document your efforts.

- Keep your supervisors updated on how the shortages are effecting your students and use data.

- Keep parents in the loop as much as possible.

Advocating for appropriate services and supports and the argument for a TODHH

- Nothing happens without data. Make sure you are collecting evidence to support your recommendations. Qualitative or anecdotal evidence is good, but quantitative (numbers) will often make a big impact. Numbers are sometimes what ‘tips the scale.’

- When a TODHH is needed, refer to the law.

Good grades do not equal progress

- Don’t use grades as your only source of information.

- When an evaluation is necessary, look at the whole student: academic, language and communication, social-emotional, functional, and level of independence.

- If student is receiving grades in classes below grade level, or if rubrics or IEP progress is being used to report how the student is performing, make sure parents know that and are reminded of it frequently.

Documentation

- Use the required format or find your own

- Timely and consistent

- Be objective

Good relationships with families

- Ask how parents would like to be kept informed, give them the best way to keep you informed (email, phone, text, class app, etc).

- Communicate regularly or make the attempt regularly

- Keep communication positive or end on a positive note – offer a possible solution or ask them for their help/advice if it’s an issue of concern

- Let parents know when good things are happening with their child.

References and More information

To read the Supreme Court’s opinion of the case see 21-887 Miguel Luna Perez v. Sturgis Public Schools

Article from ASHAWIRE see What a DHH Student’s Supreme Court Case Means for Special Education

Article from FMGLAW see Exhaustion Not Required: Perez V. Sturgis Public Schools

Written by Brenda Wellen, M.S., October 2023

Note: The information in this article does not qualify as legal advice.