Related Products

For Professionals

- Amplification

- Assessment of Student Skills, Challenges, Needs

- Early Childhood: Infants, Toddlers, Preschool

- Hearing Loss – Identification, Impact and Next Steps

- IDEA Law Summary Information

- Language and Speech Development Issues

- Legal Issues in Serving Children with Hearing Loss

- Listening (Auditory Skills) Development

- Planning to Meet Student Needs

- Self-Advocacy Skills for Students with Hearing Loss

- Self-Concept: How the Child with Hearing Loss Sees Himself

- Social Skills

- Speech Perception & Learning

Related Teacher Tools Takeout Items

Impact of Hearing Loss on Child Development and School Performance

The Impact of Hearing Loss

Because hearing loss is invisible, it is difficult understand just how much it can affect a child’s day-to-day life and lifelong potential. However, it is accepted that children who have a hearing loss are at educational risk. Parents, teachers, audiologists and other professionals should work together with the child, to understand the hearing loss and to advocate for their listening needs. This section provides information and resources about how hearing loss can impact listening, learning as well as the possible social impact of hearing loss.

Hearing Loss as a Spectrum:

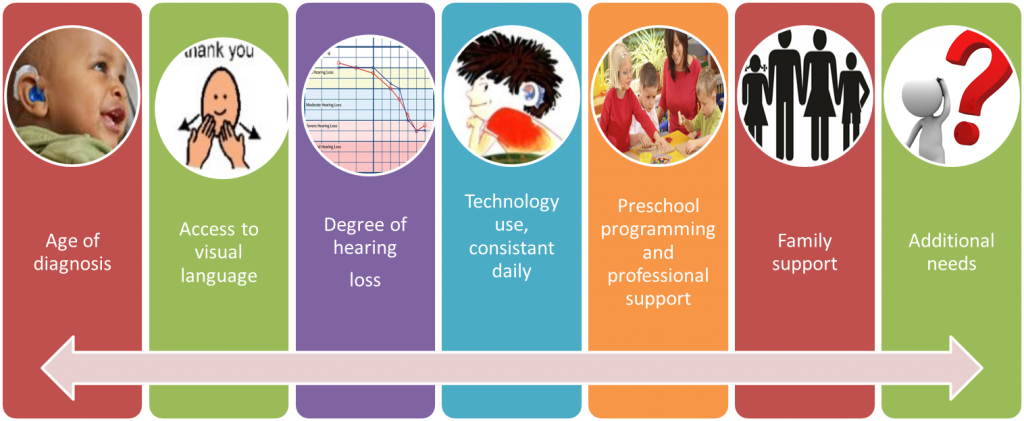

Factors that may influence the impact of a hearing loss

Although two children might have similar hearing loss on paper, their history and experience will play a huge part in their success. That is to say, two children with an identical looking hearing loss can experience very different outcomes based on a number of variables.

While previous experience teaching a student with hearing loss is indeed very valuable, the same interventions and supports may not apply to the next student you teach with a hearing loss. These are some of the contributing factors that will impact the development and learning for each individual.

Image by: Sarah Burns

Age of Diagnosis

With early detection programs this is less of an issue than it used to be but there are still hearing losses that are undiagnosed until later in childhood. A late diagnosis of hearing loss means that, for the critical language development years of life, children will have reduced access to the speech and language in their environment. This reduced access affects the foundations of language, vocabulary and literacy and is impacting the child’s:

With early detection programs this is less of an issue than it used to be but there are still hearing losses that are undiagnosed until later in childhood. A late diagnosis of hearing loss means that, for the critical language development years of life, children will have reduced access to the speech and language in their environment. This reduced access affects the foundations of language, vocabulary and literacy and is impacting the child’s:

- – Background knowledge

- – Functional language

- – Curriculum vocabulary/concepts

- – Possibly reading comprehension and written expression

The earlier the hearing loss is identified, the earlier intervention can begin. This results in earlier and the more likely delays in speech and language development may be reduced.

Access to Language – Auditory or Visual

For children who are deaf and do not use their hearing or speech to communicate, early access to consistent, closely presented verbal language and/or visual language is imperative. Simms et al. states that children need access to language that is abundant, interactive and consistent A rich language model will then facilitate accurate, appropriate and complete language development.

Degree of Hearing Loss

Any degree of hearing loss is educationally significant

, however the severity of the hearing loss can have an impact the amount of auditory information available to the child. See below for the impact of differing degrees of hearing loss.

Daily and Consistent Use of Technology

When a student does not consistently wear their hearing technologies they are denying themselves equal access to:

When a student does not consistently wear their hearing technologies they are denying themselves equal access to:

- – The auditory curriculum (lectures, videos, collaborative learning, etc)

- – The social language and interactions of his peers

- – Incidental language learning – through which 80-90% of vocabulary is attained

Incidental Exposure to Language

Hearing technologies provide incidental and direct access to words, vocabulary and auditory information. Without the daily and consistent use of hearing technologies children’s brains will not have adequate auditory input to create strong neural pathways (connections from the ear to the brain).

Example:

If a child only wears their hearing technologies while at school, that equates to approximately 30 hours per week. Assuming that a child is awake for about 135 hours per week, that is only 22% of the time. This means only 22% access to incidental words, vocabulary and auditory information. By only wearing their hearing aids at school, students reduce their access to information by almost 80%!

Programming and Professional Support

Programming support for children with hearing loss is critical. Even students who perform above their grade level require accommodations to ensure that they have equal access to the curriculum. These supports are not required because of a child’s reduced ability but rather their reduced access. Professional support could include an Educational Audiologist, a Teacher of the Deaf/Hard of Hearing, Speech Language Pathologist, etc. Refer to

Why Involve the Teacher of the Deaf.

Family Support

Family support is a key element in creating positive

self-identity

and

self-determination

is there a supporting success self-determination page? If not can there be?, which play critical roles in a child’s success as they progress through their educational careers. Youth need programming, professionals and family support to help them recognize, accept and understand their hearing loss, take responsibility for and advocate for themselves.

The Impact of Hearing Loss in School

Where above are some of the factors that may influence the impact of a hearing loss, below are some the impacts that a hearing loss may have on listening, learning and communication within the educational environment.

ACCESS

The most significant impact of hearing loss is ACCESS. Children spend much of their day engaged in either active or passive listening as a means of obtaining information – in fact ‘overhearing’ is how we learn the bulk of our vocabulary. Students with hearing loss do not have the same

The most significant impact of hearing loss is ACCESS. Children spend much of their day engaged in either active or passive listening as a means of obtaining information – in fact ‘overhearing’ is how we learn the bulk of our vocabulary. Students with hearing loss do not have the same

access to information as their peers and are not privy to ‘overhearing’ speech and language. Even with the use of hearing technologies, their access to information is impacted. As a result, background knowledge is weaker, which ultimately impacts the receptive and expressive vocabulary bank.

If a child/student does not have access to all of the speech sounds they will mishear sounds and words. For example, the words walk, walked, walks, talk, talked, talks, top, topped, tops may all sound the same. As a result the student with a hearing loss, loss must put forth

considerable listening-effort when simply trying to hear the sounds of each word. Even so, they may or may not be able to do this accurately which then requires the use of context to infer meaning. While using context to infer meaning is a fantastic strategy it is also A LOT of work; work and effort that are not required of students without hearing loss. Additionally, if the student’s background knowledge is weak, using context may not be beneficial. Now imagine experiencing all of this

continually throughout the school day (from both teachers and peers), knowing that you will be asked questions about content and required to participate in discussion.

Example:

As a student with a hearing loss Andrew will require lip-reading, context and background knowledge to ‘fill in the blanks’ in attempt to comprehend what was heard. Similar sounds are often confused or missed altogether. For example, the words ‘mother’ and ‘brother’ could be easily mistaken for each other in a sentence and Andrew would have to use the context of the sentence to figure out which word was used. For example, during an English lesson regarding Shakespeare’s play, As You Like It, the teacher could say:

“Let’s think about Duke Senior’s brother and his usurper, Celia’s father. Who here can tell me what roles these two characters have on Duke Senior? How have they helped shape his character?”

If Andrew is having to use context to figure out whether the word ‘brother’ or ‘mother’ was used (he has to relate it to the book and decide which of the two makes more sense in this instance), he cannot be actively listening to the rest of the question. Additionally, a student with reduced background knowledge due to a hearing loss is also unlikely to have been exposed to a word like ‘usurper’ and will expend energy attempting to identify the word. By the time the teacher has finished providing instructions, Andrew is likely unable to participate in the discussion.

- Tiredness in Deaf Children

- Listening Fatigue and Unilateral Hearing Loss

- Informal Assessment of Fatigue and Learning

Auditory Bombardment

Through their hearing technologies, students with hearing loss are being constantly bombarded by auditory stimulation. Hearing technologies are a necessity for access to sound however, unlike the student without hearing loss, they are unable to simply ignore unwanted sounds, since this is exactly what the hearing technologies emphasize. This constant bombardment of auditory information is a source of fatigue.

Identification of Speech Sounds

Students without hearing disorders are able to identify speech sounds with little effort. This affords them the ability to discriminate between similar sounding words without the need for additional cognitive effort. Students with hearing disorders must spend much of their energy simply identifying the speech sounds as illustrated in the ‘mother vs. brother’ example above. The extra energy required for the identification of speech sounds is a source of fatigue.

Auditory-Cognitive Closure

If some speech sounds are unable to be heard, students without hearing loss use a process called

auditory cognitive closure to figure out the meaning. E.g: “I stir my coffee with a __oon.” Because of our background knowledge and experience we don’t actually need to hear the /sp/ sound to know that “oon” was actually the word “spoon”. This is called

auditory cognitive closure and it occurs without our thinking about it. As previously mentioned, students with hearing loss often have reduced background knowledge with then impacts their ability to repair the auditory message and they are therefore unable to

auditorily close the message accurately. As a result students with hearing loss often live with a high degree of ambiguity and are continually rethinking the message. For example, “Did she say 56 or 5/6ths?” This continual rethinking is a source of fatigue.

Cognitive Load

Students with

Students with

out hearing loss use little cognitive energy on identification of sounds. Therefore, when learning new content, they are able to allocate the most of their energy to the processing and storage of this new information. Conversely, students with hearing loss use the majority of their cognitive energy on identifying the speech sounds, leaving little for processing and storage. The difficulties experienced by the hard of hearing listeners are especially pronounced in a task with high attention and memory demands thereby placing a greater cognitive load on the student with hearing loss compared to that of their peers. Katherine Bouton, a journalist with hearing loss who publishes in the New York Times, describes cognitive load as “

the brain is so preoccupied with translating the sounds into words that it seems to have no processing power left to search through the storerooms of memory for a response.

” Additionally, this increased cognitive load also becomes a source of fatigue.

Stress and Learning

Most students without hearing disorders are able to ignore background noise, identify speech sounds, use background knowledge to close gaps in the auditory message and process and store new information. Most importantly they generally do this without giving thought to the process nor do they find it stressful. Students with hearing disorders however, constantly think about this process – how they are likely mishearing and the potential academic and social ramifications of this misunderstanding. As a result students with hearing disorders reportedly find listening and learning an extremely stressful activity, unfortunately one that consumes the majority of the school day. This stress is also a source of fatigue… not to mention the research that suggests that during times of stress, learning is unable to occur.

Most students without hearing disorders are able to ignore background noise, identify speech sounds, use background knowledge to close gaps in the auditory message and process and store new information. Most importantly they generally do this without giving thought to the process nor do they find it stressful. Students with hearing disorders however, constantly think about this process – how they are likely mishearing and the potential academic and social ramifications of this misunderstanding. As a result students with hearing disorders reportedly find listening and learning an extremely stressful activity, unfortunately one that consumes the majority of the school day. This stress is also a source of fatigue… not to mention the research that suggests that during times of stress, learning is unable to occur.

link

ACADEMICS

Many of the issues that impact the fatigue level of students with hearing loss, can also impact academic performance.

Sound Identification

The inability to hear certain sounds can most certainly impact understanding this will have an impact on a student’s

The inability to hear certain sounds can most certainly impact understanding this will have an impact on a student’s

spelling, reading and/or phonemic awareness skill development.

Not hearing the quieter and higher pitched sounds /s/, /sh/, /th/, /f/, /t/ will have an impact on

plurals, possessives, ordinals, verb-noun agreement and the subtle nuances of speech

(e.g. the cat drinks vs. the cat’s drink).

Listening in Background Noise:

The inability to hear high pitched sounds makes listening in any amount of noise (even quiet classroom chatter) EXTREMELY challenging. This is especially true for

classroom discussions and group/partner work

, when classroom noise is known to be at its height.

Cognitive Load

Increased cognitive load will impact a student’s ability to

follow multi-step instructions, pay attention, and may affect note taking.

Because students with hearing loss use speech reading (lip reading) cues to fill in gaps of missed information multiple processes must be in place when taking notes, which also increased cognitive load:

- – listening to teacher speak through their personal FM system

- – Ignoring even small amounts of background noise

- – lipreading

- – looking at the board

- – processing new information

- – writing notes

This is a challenging if not impossible feat. While students with normal hearing are able to look at their papers and write while listening, students with hearing loss must watch their teacher’s lips and face for supplementary visual cues and then write down what was heard (which may or may not be accurate). However this requires diverting visual attention from the teacher (for reading lips) and the student may then miss what is being said. By the time the student is writing the initial piece of verbally presented information, the teacher has already moved on to the next piece or topic. Students with hearing loss often state that they miss large pieces of information as they are always trying to ‘keep up’.

This is a challenging if not impossible feat. While students with normal hearing are able to look at their papers and write while listening, students with hearing loss must watch their teacher’s lips and face for supplementary visual cues and then write down what was heard (which may or may not be accurate). However this requires diverting visual attention from the teacher (for reading lips) and the student may then miss what is being said. By the time the student is writing the initial piece of verbally presented information, the teacher has already moved on to the next piece or topic. Students with hearing loss often state that they miss large pieces of information as they are always trying to ‘keep up’.

Background Knowledge/Vocabulary

The weak background knowledge and vocabulary will impact a student’s ability to understand

new concepts, challenging vocabulary, multiple meaning and idiomatic language.

Listening Effort and Fatigue

The listening effort and resultant fatigue will impact a student’s ability to

follow long conversations and remember information/instructions.

See

Accommodations for Students with Hearing Loss

for programming suggestions related to these academic issues.

CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

While school aged children are required to hear their teacher for the majority of their curricular content, there are many other listening, learning and social situations that can be impacted by a hearing loss.

Beginning Statements & Morning Announcements

There is a lot of auditory information provided at the start of the morning which is a challenging time for kids who are hard of hearing. Beginning statements are often missed while the teacher hasn’t quite gotten to putting the FM system on or is just putting on while addressing the class. Additionally, announcements are almost impossible for DHH students to understand as school PA systems are notoriously distorted.

Auxillary Audio

Access to audio sources other than the teacher is increasingly becoming a barrier to the curriculum. Challenges include: listening centers, computer based learning/assignments and audio from Smartboards (videos).

Access to audio sources other than the teacher is increasingly becoming a barrier to the curriculum. Challenges include: listening centers, computer based learning/assignments and audio from Smartboards (videos).

Collaborative Learning

Feilner and her colleagues found that hard of hearing students reported that hearing their teachers (when using the FM/DM system) and working individually to be the least challenging listening activities during the school day.

The most challenging of the listening situations were reported to be group/partner work, interactive lessons and class discussions – which made up about a 1/3 of the listening day. A personal FM/DM on the teacher just isn’t enough because the DHH students miss out on peer interactions – which, with an increased move toward collaborative learning, project based learning, and as they move upwards throughout the grades, become critical learning opportunities.

The most challenging of the listening situations were reported to be group/partner work, interactive lessons and class discussions – which made up about a 1/3 of the listening day. A personal FM/DM on the teacher just isn’t enough because the DHH students miss out on peer interactions – which, with an increased move toward collaborative learning, project based learning, and as they move upwards throughout the grades, become critical learning opportunities.

Field trips and Sports

For younger students the most troublesome activities were center time and “exciting activities”, identified as recess, gym, field trips, etc.

Transitions and Topic Changes

As students progress through the grades teachers often underestimate the importance of transitions. Changes in activities and changes in topic throw hard of hearing students off course. This is even more true during interactive or collaborative lessons since

interactive classroom discussions often create a course of their own. Good teachers follow that path, which can result in straying away from the topic at hand.

The Impact of Hearing Loss on Social Communication

Students with a hearing impairment may feel isolated in the school environment and can find the aggressive social structure difficult to navigate. Some environments that can be challenging include hallways, boot/coat rooms, recess, lunch and the bus. Tween/teen language may be particularly difficult to understand as they often socialize while engaging in another activity such as eating, are prone to the use of slang and idioms, and may mumble or yell in the course of a conversation.

Students with a hearing impairment may feel isolated in the school environment and can find the aggressive social structure difficult to navigate. Some environments that can be challenging include hallways, boot/coat rooms, recess, lunch and the bus. Tween/teen language may be particularly difficult to understand as they often socialize while engaging in another activity such as eating, are prone to the use of slang and idioms, and may mumble or yell in the course of a conversation.

I Brought it to the Kitchen Table

The Ida Institute video,

I Brought it to the Kitchen Table (scroll down) highlights how social isolating a hearing loss can be – in a student’s own words.

The article below was written by a 14-year-old student with a mild-to-moderate hearing loss in one ear and a moderate loss in the other, who uses bilateral hearing aids to access sound. He has always been the only student in his school with a hearing loss. He is active in sports, has good friends and does well in school. He was the first student with hearing loss in memory to be accepted into the gifted and talented program in his local area while in elementary school. When this was written, in 2010, he attended junior high and hoped to be a marine biologist or veterinarian someday. While he gets good grades, he has to work hard to do things that his friends who have typical hearing take for granted. The stress and frustration can be overwhelming. With each new school year, he faces the challenges of unfamiliar teachers who probably have never worked with a student who is deaf or hard of hearing before, and classmates who have never had a peer with a hearing loss. Most of his teachers have been supportive and have gone above and beyond to accommodate his hearing loss. But every year, new problems pop up and he has to learn to cope. And, as been true his whole life, he starts each year as the only kid in school with a hearing loss.

My life as the only student who is hard of hearing in my school can sometimes feel like a bottomless pit of confusion. It is not always that bad, but it is a struggle. I miss a lot of sounds. I often don’t even know if I have missed a sound, sometimes at my own expense. My life at school is defined by what I hear, what I don’t hear and how I learn to cope with the differences.

When I meet new people, they do not always notice my hearing aids. They often do not understand why I do things in a different way, and it may seem weird to them. They will shout at me because they think I am doing something wrong, even though it is just the way I do things. Sometimes, even when they do notice my hearing aids, they will still shout at me. They think I am just being “difficult” or I am lying about my hearing loss. They think I am dumb or don’t have any “feelings” because I can’t hear well.

In school, I struggle with how some teachers act. They cannot seem to adjust to having a student who is hard of hearing. For example, even though my parents and I have asked them not to, they will do things like speak facing the board and not toward the class. The sound just bounces off the board and away from me. I can only hear a bit of what they say. I can’t understand those lone bits of sound if they don’t talk to me.

Teachers will also sometimes change assignments orally and I will miss what they say. Then, when I turn in the assignment, I get marked down or get an “incomplete” grade, even if I have everything else correct. This makes me feel sad and confused because I try so hard, but I don’t seem to meet their standards. It is not that I cannot do the work, but I need to do it my way. It takes a lot of extra energy to do simple things, like listen to a lecture or take notes on a video that is not closed-captioned. If I cannot see the notes or the information the teachers are trying to pass on to me, I find it harder to understand.

I have learned how to cope with the frustrations of being hard of hearing. I spend time with family and friends who understand me. I am also active in sports, like basketball, soccer and tennis, and that helps, but it is not without problems. Occasionally while playing basketball, I will receive a technical foul because I cannot hear the referee, and once a soccer coach threatened to kick me off the team because I couldn’t hear him.

Surprisingly, there are some advantages to being hard of hearing. When I sleep without my hearing aids, noises don’t wake me up. I sleep well and have lots of energy when I wake up. The only bad part, of course, is actually having to get up. In school, I find it easy to focus when I take my hearing aids out. Also, I can turn my hearing aids off if my parents are nagging me. Of course that just makes them mad but, after all, I am a little bit of a teenager (but not too much of one).

There are advantages and disadvantages to being the only student who is hard of hearing in my school. Once I explain my hearing loss, most people understand and treat me fairly. Good teachers, good coaches and other school officials have helped me thrive. I have challenges to overcome, but so does everyone else, each in their own way. I may be the only kid who is hard of hearing in my school, but as I listen to the lone sounds of my life, they tell me I am not alone.

Source:

Volta Voices, May/June 2010; updated January 2016.

References:

Meister, H. et al. (2016). Effects of Hearing Loss and Cognitive Load on Speech Recognition with Competing Talkers. Frontiers in Psychology. 7:301.

See full article

here

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4777916/.

Vogel, S. & Schwabe, L. (2016). Learning and memory under stress: implications for the classroom.

npj Science of Learning 1, Article number: 16011

Resources:

Cholesteatoma – What is it and how can it effect learning?

Starting School LIFE (Listening Inventory For Education)

Children’s Home Inventory for Listening Difficulties (CHILD)

Downloadables:

Why Involve the Teacher of the Deaf.

This page was created August 2017. Our sincere thanks to Krista Yuskow, educational audiologist, Edmonton AB for her expertise in compiling this information.