Related Products

For Professionals

- Amplification

- Assessment of Student Skills, Challenges, Needs

- Early Childhood: Infants, Toddlers, Preschool

- Hearing Loss – Identification, Impact and Next Steps

- IDEA Law Summary Information

- Language and Speech Development Issues

- Legal Issues in Serving Children with Hearing Loss

- Listening (Auditory Skills) Development

- Planning to Meet Student Needs

- Self-Advocacy Skills for Students with Hearing Loss

- Self-Concept: How the Child with Hearing Loss Sees Himself

- Social Skills

- Speech Perception & Learning

Related Teacher Tools Takeout Items

Evaluation Considerations – Low Average ≠ ‘Okay’

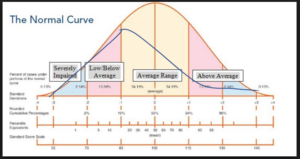

The abilities of children with hearing loss, whether they are exiting from early intervention or are already school-aged, are typically evaluated to identify overall delays or learning disorders. Since children with hearing loss have access issues learning language due to barriers caused by the hearing loss, they often score ‘low-average’ on norm-referenced language tests. Rather than having overall delays, the access issues caused by hearing loss often result in ‘spotty skills’ or learning gaps that are not identified by typically used evaluation instruments. Because these needs are not identified by typical measures, our students are often denied eligibility for specialized instruction and supports. The specialist in education of students with hearing loss needs to be a member of the evaluation team to help tailor the assessment process to identify the unique needs of these children.

Research has consistently revealed that a ‘good’ result of early intervention for children with hearing loss is a standard score of -1 SD to -1.5 SD on norm-referenced language tests (standard score 78-88 range). All too often teachers of the deaf/hard of hearing have sat in meetings where the evaluation team has described these results as ‘normal’ and ‘he will be okay.’ After all, special education is not preventative, it is for children who have identifiable disabilities. ‘Low-normal’ does not equal a disability. Yet professionals who work with these students realize that there ARE language issues, including ‘Swiss cheese language’ which influences comprehension, delays in syntax learning, and in early literacy skills.

Using Norm-Referenced Tests to Determine Eligibility

The purpose of the testing is to identify an educational disability or adverse educational effect on educational performance. For children with hearing loss, assessment needs to be sufficient in scope and intensity to identify gaps in auditory (or sign language development), language, narrative discourse, academic, literacy, and social language skills. Information needs to be collected that reflects the student’s ability to function in situations similar to the school setting, including typical use of amplification.

Norm-referenced tests typically have various subtests, each of which assesses one type of ability area. These subtest scores are rolled together into an overall or total score for the norm-referenced test. It is often claimed that only the overall score from the norm-referenced test can be used to determine eligibility. This is frustrating to persons who work with students with hearing loss as there are often one or more subtests that show areas of need, but the overall score average is within the acceptable range. Section 300.304(b)(2) of IDEA states that a single measure or assessment cannot be used as a sole criterion for eligibility. So yes, a single subtest score cannot be used to determine a child as eligible. This is misleading. If the area of need identified by the low performing subtest(s) was also demonstrated by other norm-referenced and/or functional measures, then the child’s area of need would have been demonstrated with more than one measure. If there is a substantial need identified, go the extra step to verify it. This can make the difference between eligibility for supports and services or no specialized help for the child. For more discussion on using subtest results to determine the need for further testing, read here.

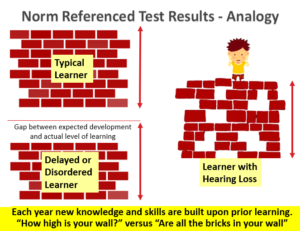

Another aspect of norm-referenced testing is that the measures are designed to identify areas of delay or disorder. To use an analogy, we can compare the knowledge and skills learned each year to a row of 12 bricks to build a wall.  Every year there would be a row built up, starting from infancy. Think of each brick as collectively representing vocabulary and concepts learned during one month of exposure. Consider our students who did not consistently use amplification, or were not consistently exposed to fluent sign, during early childhood and how that would impact their ‘row of bricks development’ as compared to typically developing hearing peers. Norm-referenced tests, specifically the overall scores, consider development as ‘How high is the wall?’ as compared to typical learners. Children who have cognitive delays or learning disorders would have shorter walls. Children with hearing loss are typically found to have walls almost as high as their age peers (low average) but what is NOT identified is the gaps in learning that are typical of children with hearing loss due to communication access limitations that vary over time.

Every year there would be a row built up, starting from infancy. Think of each brick as collectively representing vocabulary and concepts learned during one month of exposure. Consider our students who did not consistently use amplification, or were not consistently exposed to fluent sign, during early childhood and how that would impact their ‘row of bricks development’ as compared to typically developing hearing peers. Norm-referenced tests, specifically the overall scores, consider development as ‘How high is the wall?’ as compared to typical learners. Children who have cognitive delays or learning disorders would have shorter walls. Children with hearing loss are typically found to have walls almost as high as their age peers (low average) but what is NOT identified is the gaps in learning that are typical of children with hearing loss due to communication access limitations that vary over time.

To combat this, the person specializing in the education of children with hearing loss needs to be part of the evaluation team (IDEA Section 300.321(4)(i)(5)). We need to press for evaluation in the areas that we know are at highest risk for issues due to the impact of hearing loss. In looking at the list below, it is clear that the test battery typically used by the school team to evaluate children suspected of learning disorders will not capture the most likely areas of need for students with hearing loss. Moreover, we need to work with the team to discuss evaluation measures that can provide the norm-referenced results of the specific skills needed to tailor the assessment to specific areas of educational need, as required by IDEA (Section 300.304(c)(2)). Refer to Steps to Assessment for information on specific measures.

Areas of learning most likely to be impacted by hearing loss:

- Understanding group discussions or participating in small group work due to distance/noise in class and socially

- Vocabulary: Gaps due to decreased ability to overhear incidental language (‘Swiss cheese language’)

- Syntax: Incomplete understanding of rules (i.e., cannot hear /s/ or /ed/; do not understand plurals, possessives, past tense)

- Working Memory: ability to retain fragmented parts of words heard and new spoken/signed vocabulary

- Listening skills: Can be challenges with simple discrimination of sounds, phrases or comprehension of conversation or verbal instruction in class (they may hear but not process the full meaning)

- Attention: Periodic inattention due to listening fatigue and gaps in understanding; ‘tuning out’ when it is challenging

- Early reading: Phonology/phonemic awareness issues related to not distinctly hearing speech sounds

- Language processing: due to fragmented hearing, vocabulary gaps, syntax and morphology gaps, slower listening rate, reduced understanding words in context

- Viewing information from different perspectives, understanding emotions of others, critical thinking

- Social language: Socially awkward, delays in pragmatic language, nonverbal social cues, and appropriate peer interactions

- Passive or immature skills in responding when they do not understand what was said; lack of self-advocacy

Influence of CONSISTENT use of hearing devices on language outcomes: Consider our students who did not consistently use amplification, or were not consistently exposed to fluent sign, during early childhood and how that would impact their ‘row of bricks development’ as compared to typically developing hearing peers. Children with more consistent DAILY hearing aid use have better language and auditory outcomes than children with less consistent use, averaging 2/3 of 1 standard deviation difference2. This is especially true for children with hearing loss of 41-70 dB. If children with hearing loss already perform in the low average range for language, an additional 2/3 of 1SD delay can make a lifelong difference in school outcomes. Consistent hearing use is a big key to protecting against language delay and catching up or keeping up with language/learning.

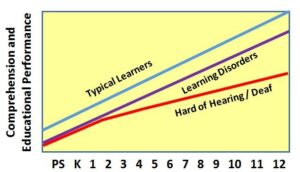

A Predictable Downslide in School Performance: With exposure to a dynamic language environment in a structured classroom setting, many typically hearing children who have low-average language ability can begin to catch up to their more average peers.  This assumption cannot be applied to children with hearing loss. A dynamic classroom language environment typically provides less access to communication than what the child experienced in early childhood. It is typical for our students to have their learning trajectory decrease once they enter school, meaning their rate of learning actually declines due to increased issues clearly accessing communication. If a child was not made eligible for specialized instruction, be sure that a 504 Plan is developed and include periodic monitoring by a DHH specialist as part of the necessary auxiliary aids and services (education in regular classes with supplementary services, read FAQ 4).

This assumption cannot be applied to children with hearing loss. A dynamic classroom language environment typically provides less access to communication than what the child experienced in early childhood. It is typical for our students to have their learning trajectory decrease once they enter school, meaning their rate of learning actually declines due to increased issues clearly accessing communication. If a child was not made eligible for specialized instruction, be sure that a 504 Plan is developed and include periodic monitoring by a DHH specialist as part of the necessary auxiliary aids and services (education in regular classes with supplementary services, read FAQ 4).

An evaluation team has the responsibility to appropriate assess students to identify areas of need that will interfere with educational performance. To this end, IDEA Section 300.304 requires that teams gather relevant functional, developmental, and academic information about the child. Academic information is only one part of educational performance. This is especially important for students with hearing loss who often have functional performance issues related to decreased access, such as challenges following directions, participating in group work, listening comprehension, and fatigue. These are all relevant functional performance issues that must be considered when evaluating a student’s need for specialized instruction and support.

References

1. Spencer, P., & Marschark, M. (2010). Evidence-Based Practice in Educating Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students. “Children who are identified early and receive early intervention have been found to demonstrate language development in the “low average” level compared to hearing children.” (pg 42) Read more about book.

2. McCreery R. W., Walker E. A., Spratford M., et al. (2015). Longitudinal predictors of aided speech audibility in infants and children. Ear Hear. 36:24S–37S Go to article.